Feb. 2, 2017 – Stephanie Kuo –

‘You can’t talk about homelessness without talking about race’

Over the past year, the city of Dallas has gradually shut down the homeless encampments near Fair Park – where hundreds lived under highway bridges. Cindy Crain is the CEO of the Metro Dallas Homeless Alliance and a member of the KERA Community Advisory Board. Her organization spearheaded those closures. She’s been working with the homeless for years, and yet, some things still surprise her.

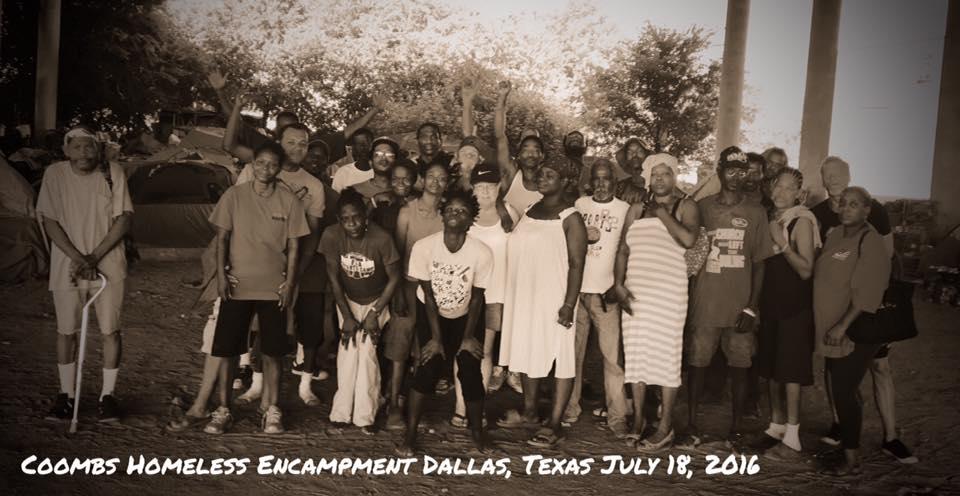

“It was when the Coombs encampment was closed. I asked everyone if I could take their picture, and they all gathered up and we took a group photo,” Crain said. “And it was stunning because it was such a blatantly, obviously and extraordinary amount of persons of color, black folks of Dallas, living under bridges compared to other ethnicities and races”

That racial disparity forced Crain to confront gaps in the city’s approach to helping the homeless. Her group recently received a $32,000 grant from United Way of Metropolitan Dallas to join a national initiative on racial inequity.

“It should impact how we apply our services and distribute resources,” Crain said. “You can’t talk about homelessness without talking about race. You have to look at those numbers because they don’t add up.”

‘You still have systems that continue to produce racist results’

About 13 percent of America is black — yet black people make up nearly 27 percent of those in poverty and more than 40 percent of the homeless living in shelters, according to census data. In Dallas, that number is 70 percent.

“A disproportionality like that sort of immediately speaks to a systemic issue,” said Marc Dones, associate for inequity initiatives and diversity at the Center for Social Innovation – a national social justice group that works with vulnerable communities.

“Black people are about three times more likely than white folks to experience homelessness. The only group that comes close to that is Native Americans, who are about two times more likely to experience homelessness,” Dones said. “I would enjoin us to always remember that disproportionality, as an output of our systems, always points to injustice.”

Dones said individual circumstances alone can’t account for the rates of poverty and homelessness in people of color.

“We have had extremely racist housing policy in this country, going back to institutional redlining that didn’t officially end until 1968 that blocked folks of color, particularly black folks, out of purchasing homes through federally backed mortgages that led to ghettoization. We had blockbusting. We had the urban renewal projects, which drove black people out of cities and into other ghettos,” he said.

Residential maps of Dallas in the 1930s show that swaths of nonwhite, poor neighborhoods were redlined, which led to disinvestment and decline in those communities. Over several decades, many black families were forced into substandard living conditions. Those who moved into South Dallas, which at the time was predominantly white, had their homes firebombed, burned, and vandalized. Decades of employment discrimination and segregation exacerbated the problem, Dones added – the effects of which are still felt today.

“We did no work to systematically audit and change our systems away from being racist. You still have systems that continue to produce racist results,” Dones said. “We had 250 years of institutionalized slavery in this country, 89 years of institutionalized apartheid. So when we talk about how long black folks and folks of color have had even nominal access to these systems, we’re talking about well within a single human lifespan so the idea that any large changes would’ve happened, it just doesn’t make sense.”

Housing advocates say the city has had a long struggle with landlords discriminating against tenants with Section 8 housing vouchers – most of whom are black.

‘Homelessness is a systematic breakdown, not a personal failing’

In 2013, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development accused the city of knowingly misusing federal funds to promote racial segregation in public housing. The issue is still ongoing. Dallas officials have said they do follow federal housing guidelines, but some city council members have said the accusation serves as a reminder that public housing is still overwhelmingly concentrated in South Dallas, which is now home to some of the city’s poorest residents, where there’s been unequal access to quality jobs, education and even grocery stores.

As part of its research, the Center for Social Innovation is collecting personal stories to help better understand how people become homeless.

“Homelessness is a systematic breakdown, not a personal failing,” said Jeff Olivet, CEO of the Center for Social Innovation. “To unpack homelessness and to end homelessness, you’ve got to come at it from a multi-systems point of view, and we believe that’s best done with a lens of racial equity. That’s not to say that homelessness is only about race – of course it’s not, it’s about a 100 other things as well, but there is a dimension of racial equity that we need to be addressing.”

Derrick Golette agrees. He could be one of those stories. He’s black and a single father to 10-year-old Derrick Jr. He currently lives at Family Gateway, which provides transitional housing in Dallas, and he’s working as a certified nursing assistant.

“Right now, I have an apartment, and now all I’m waiting for is the Section 8 people to get with the apartment and say, ‘hey we did the check, and it’s good.’ And they call me and tell me when to come in and pick up the key and move forward,” Golette said.

Golette is 50 years old and had to move into a homeless shelter, juggling his finances and paying child support. He has four other children; two of them still rely on him. Golette’s happy he’s getting into public housing, but says the process was long and tedious, with a lot of mix ups, delays and difficult negotiations with apartment managers.

“So that’s a form of, to me, of racism or discrimination,” he said.

Golette says he’s in a much better situation than the homeless men and women he sees everyday on the street – and that’s enough motivation for him to keep working for his son.

“Me being a black man and a single father – that’s hard. I don’t tell him every day that life is roses. No, it’s not,” he said. “Every day, when [I] walk out this door in front of Family Gateway, I see the homeless people down here. And when I see it, it disturbs me. I don’t have to be out there in the streets the way they are. I’m here only by God’s grace.”

He’s moving forward now, toward stable housing and a future that feels more secure. Golette says though, he’s not so far from the homeless men he sees every day – men who look a lot like that he does.

Click here for full story.